Farewell 2009

December 30, 2009

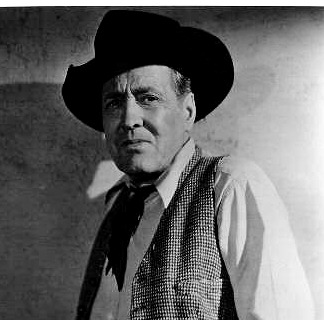

William S. Hart “The Disciple”

December 21, 2009

All of the films I’ve seen directed by and starring William S. Hart contain an element of Christianity, either directly (quoting of Psalms in the cards for “Toll Gate) or by heavy-handed allegory (everything else). I’m not sure if Hart was a believer or if he just felt that this sort of sentiment belonged in his films.

In his Dartmouth class notes, Charles Starrett lists his religious affiliation as Episcopal. I wonder if the Christian elements of Hart’s film helped to make him Charles’ favorite Western star.

Charles would have been eleven when “The Disciple” came out in 1915. For the first time that I know of, Hart plays an actual man of God. He’s Jim Houston and the card tells us he’s “The ‘Shootin’ Iron’ parson of the frontier, strong of jaw and good at prayin.'”

Charles would have been eleven when “The Disciple” came out in 1915. For the first time that I know of, Hart plays an actual man of God. He’s Jim Houston and the card tells us he’s “The ‘Shootin’ Iron’ parson of the frontier, strong of jaw and good at prayin.'”

He rides into town with his wife, daughter and bible. The good citizens have sent for a parson and Jim’s here to fill the job. His first act is to save a man from a drunken lynch mob. Doc Hardy, the saloon keeper, doesn’t like the sky pilot much, but he does like the look of his wife.

Hart made no sound films, except for the short introduction to the 1939 re-issue of 1925’s “Tumbleweeds.” However, he was a trained and successful Broadway actor not afraid of the big, dramatic roles — he famously played Ben Hur on stage. Even in silent dumb show, his sermons in this film are powerful and remind one of Barbara Stanwyck’s turn in Capra’s “Miracle Woman.” I wish I could have heard them.

He also handles a gun well, even if old “Two-Gun Bill” is short by one. He pulls it on a crowded bar and sends them to church. “Are you goin’ to force me to preach to cripples?”

Jim Houston’s religious journey is a twisted path. In short: he begins full of zeal, his wife splits with Doc Hardy, he tears it with God — “You and me is done”, he becomes a hermit in the hills, his young daughter falls ill — “You’ve struck me another blow from behind”, there’s a big storm, he falls on his knees — “God, I surrender, I surrender”, lightening takes out the roof of a nearby cabin where is wife is hiding, she seeks refuge and finds her sick child — “She must have a doctor”, there ain’t any in the county, but WAIT! DOC Hardy!

This is Houston’s enemy, the guy who stole his wife and destroyed his faith. Will he shoot him or ask him to save his daughter’s life?

A little of both. He holds a gun on the guy and MAKES him save his daughter’s life. Unlike the ending of a more typical WSH film like “Hell’s Hinges” where he gets righteously angry and burns the whole damn town down, here he forgives his wife AND Doc Hardy.

We then cut to a shot of the three crosses atop Golgatha and a card reading: “God moves in mysterious ways his wonders to perform.”

I guess he does. It’s sort of boring, though. Imagine a Clint Eastwood, or Charles Bronson, movie where Clint or Charley takes a pile of shit throughout the film and ends up forgiving his enemies. It’s like that.

So, by that count, maybe this is the most Christian of Hart’s films.

Other Cowboy Stars – Johnny Mack Brown in “Desert Phantom”

December 19, 2009

Charles Starrett and Johnny Mack Brown were friends. They apparently hung out, and, on at least one occasion, they went hunting together. In fact, they were involved in a near fatal car accident while on that hunting trip. I wrote about this here.

They may have met on the set of “Three on a Honeymoon“, a 1934 romantic comedy from Fox which I have not yet seen. From the billing, it appears that Charles and Johnny Mack Brown played supporting roles to Sally Eilers and Zasu Pitts.

I’ve seen one other Johnny Mack Brown film. That was the 1944 Monogram production “Law Men”. I was less than impressed with JMB in that film and was puzzled by his enduring popularity.

Watching this 1936 film, I understand his draw much better. He’s quick with the gun, a top rider and throws a convincing punch. He looks smart in his city-slicker-type duds up top, and pretty authentic in his lived-in cowboy clothes for the rest of the picture.

Unfortunately, this Supreme Pictures production is a loser. It’s cheap with bad sound and cruddy cinematography. As the title suggests, it has one foot in the horror genre…actually, let’s call it a toe.

Unfortunately, this Supreme Pictures production is a loser. It’s cheap with bad sound and cruddy cinematography. As the title suggests, it has one foot in the horror genre…actually, let’s call it a toe.

We meet JMB as a traveling salesman for Gigantic Shells. This allows him to show off his quick draw skills, which are considerable, and to meet a pretty gal played by Sheila Manors.

It’s getting late, so won’t he spend the night at the inn? Well, he overhears a troubling story about a ghost who is killing cowhands out at the gal’s ranch, so he rides out there and offers to work for her.

She says, “You’ll be in terrible danger.”

He says, “I’ve always been interested in ghosts and this will give me a chance to learn more about them.”

How’s that for motivation? The story lurches along with this sort of laconic drive. He quits his salesman gig. The ghost takes a shot at him. The spooky step-dad asks him if he’s ready to quit, “Kind of losing interest in your job on account of it?”

He replies, “Not at all. As a matter of fact, I figure it’s going to be right interesting.”

At some point, we discover that he has a back-story. Local thug Salazar killed his sister’s husband and JMB has been searching the country ever since, hell-bent on revenge. That is until he got more interested in finding ghosts. For a driven man, he sure changes course on the merest of whims.

Much of the final chapters of the film takes place in a cave. This set is reminiscent of the one where Durango saved Smiley in “Streets of Ghost Town.” Yep, it’s that cheap and fake looking.

Poor Johnny Mack Brown. I understand he made some mid-budget films for Universal in the late-30s and early 40’s, but he sure spent the beginning and the end of his career on Poverty Row. The cheap production value does allow for some cool invention — there’s a long, seemingly hand-held, tracking shot of a pair of muddy boots walking across the cave floor and climbing a wooden ladder. You never see that kind of camera movement in a Starrett Western.

The film also suffers from some incredibly bad storytelling. For example, when JMB finally catches the man he’s been hunting for revenge for so long, he blithely turns him over to Tenderfoot to take to the Sheriff. Why? He’s tired.

Another plotting failure involves JMB taking a nap before the final showdown. Seriously! Our hero on a couch, snuggled up under a blanket, while important things are taking place. Like plot.

Fortunately, he wakes up in time to end this stinker.

To George from Charles

December 13, 2009

We have ourselves a mystery!

Duane writes with a puzzler. His sister was given this belt buckle many years ago.

As you can see, the inscription reads “Thanks George” and “Charles Starrett.”

As you can see, the inscription reads “Thanks George” and “Charles Starrett.”

His question is: Who’s George?

His question is: Who’s George?

The story of the buckle starts with Albert Peterson, a professional clarinetist who played on many film scores. He and his wife, Bea, were very social in the Hollywood set. Bea even babysat for Bing Crosby’s kids.

Somehow, Albert acquired the belt buckle and, many years later, he retired and taught clarinet to high school musicians. He gave the belt buckle to a prize student, Duane’s sister. Albert has since passed away.

My one thought is that it might be George Chesebro, the solid character actor who appeared in 54 films with Charles Starrett.

I promised Duane I’d ask my learned readers for their thoughts. Anyone have any good ideas?